My last response concluded with the realization of how challenging it is to hold someone else’s pain. This week’s response begins with the equally difficult task of sitting with my own discomfort.

As I was unsettled by this week’s artifact, my response is less structured, less researched. It is more in the realm of feeling than of thinking.

Let me start by sharing Devora’s artifact for the prompt Unsettled.

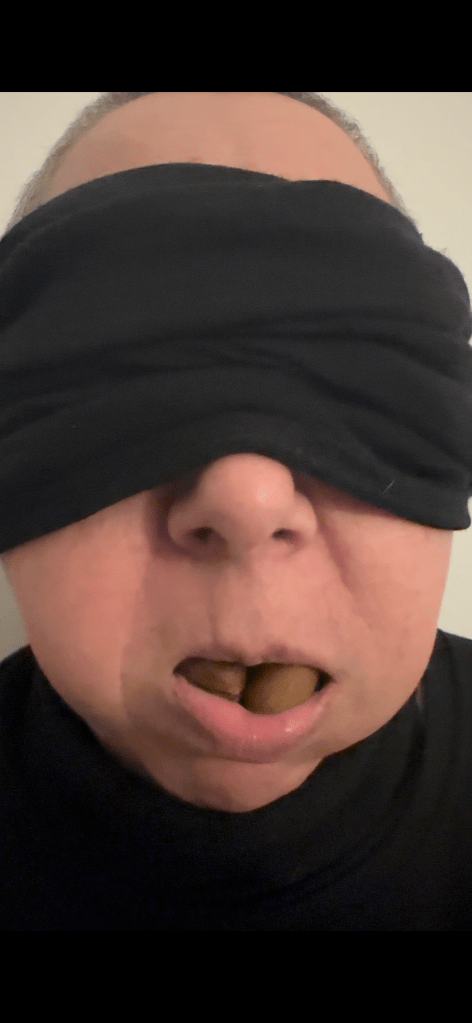

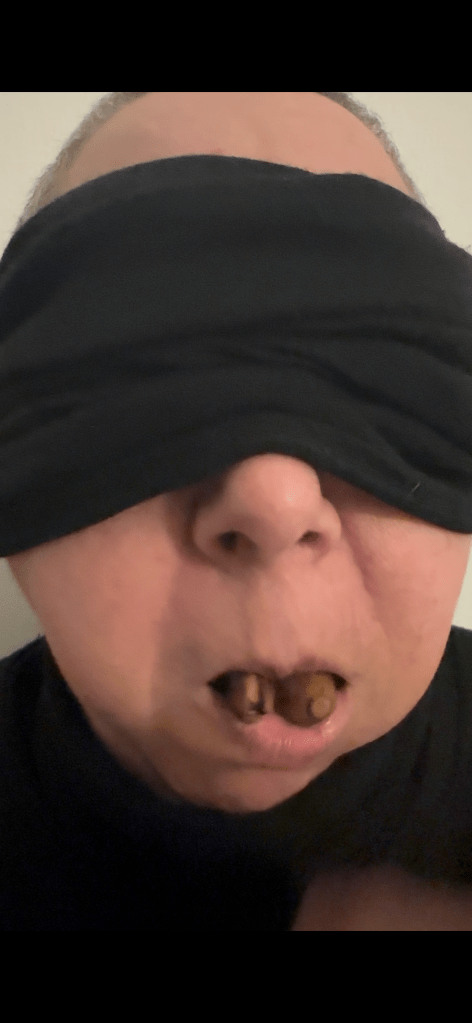

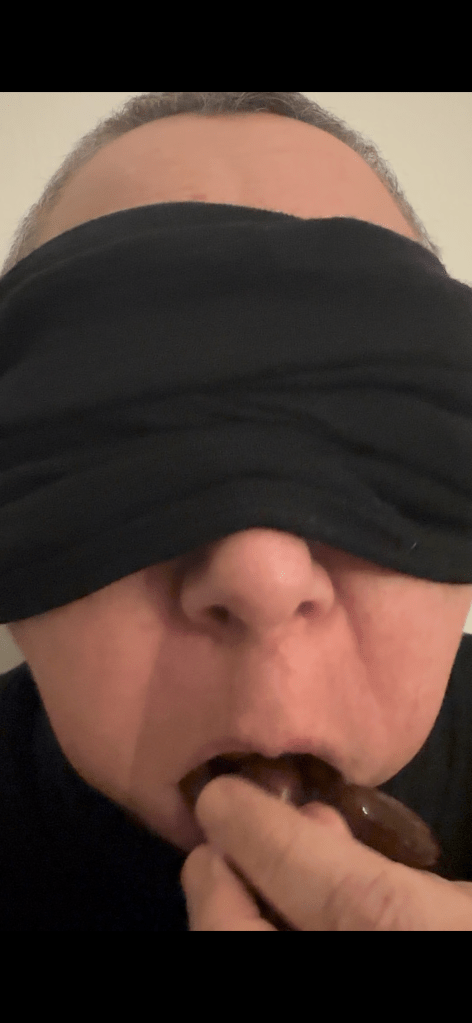

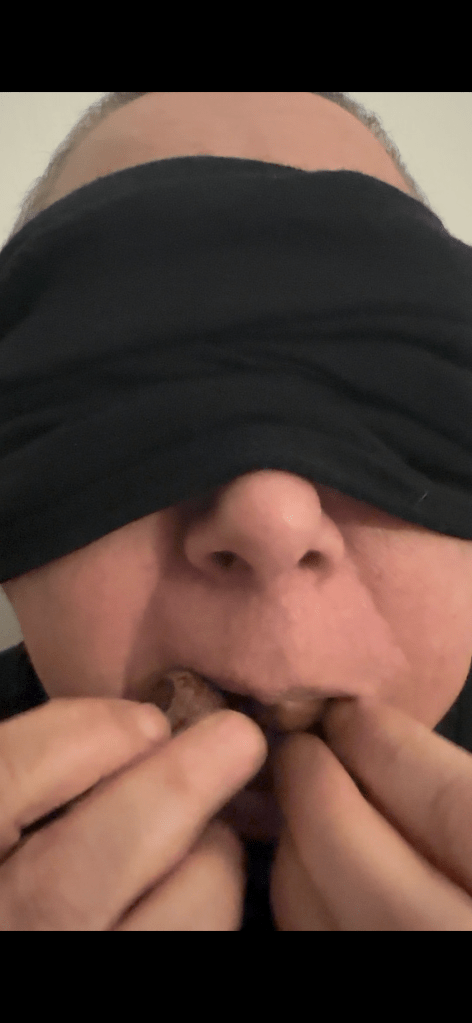

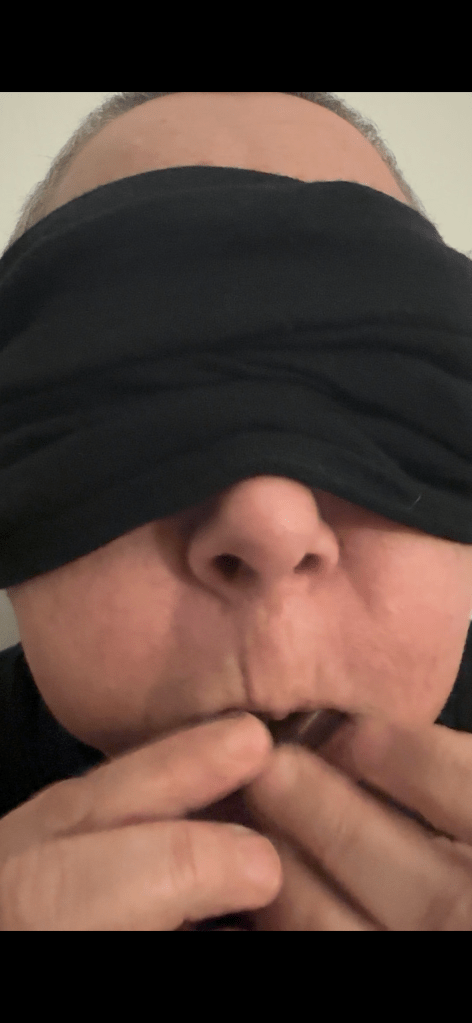

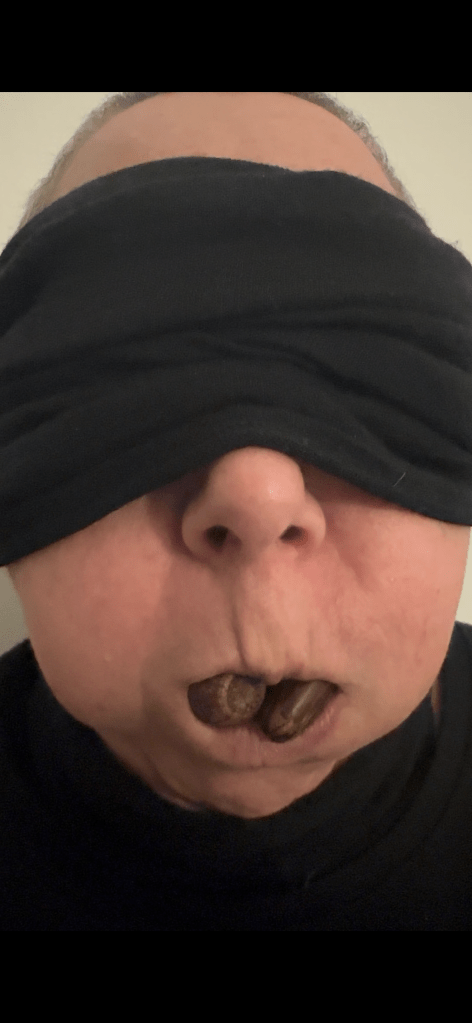

Devora explains that they have been walking along wooded pathways to and from the pool, where most of the trees are oak, which, given the time of year, have been shedding acorns across the ground. They began noticing the variety in shapes and sizes, and how smooth and weighty the acorns felt in their hands. Eventually, they started collecting them, with a clear idea of how they would use them as a response to Unsettled.

Once they had settled on the specifics of the performance gesture, they turned to ChatGPT to see if AI could assist them in making sense of their intuitive sense that this would be an appropriate response to the prompt “unsettled.”

Their exchanges was attached to the e-mail:

It was with this context that I received the video below.

I had not however read the e-mail in detail or opened the attached link before watching it.

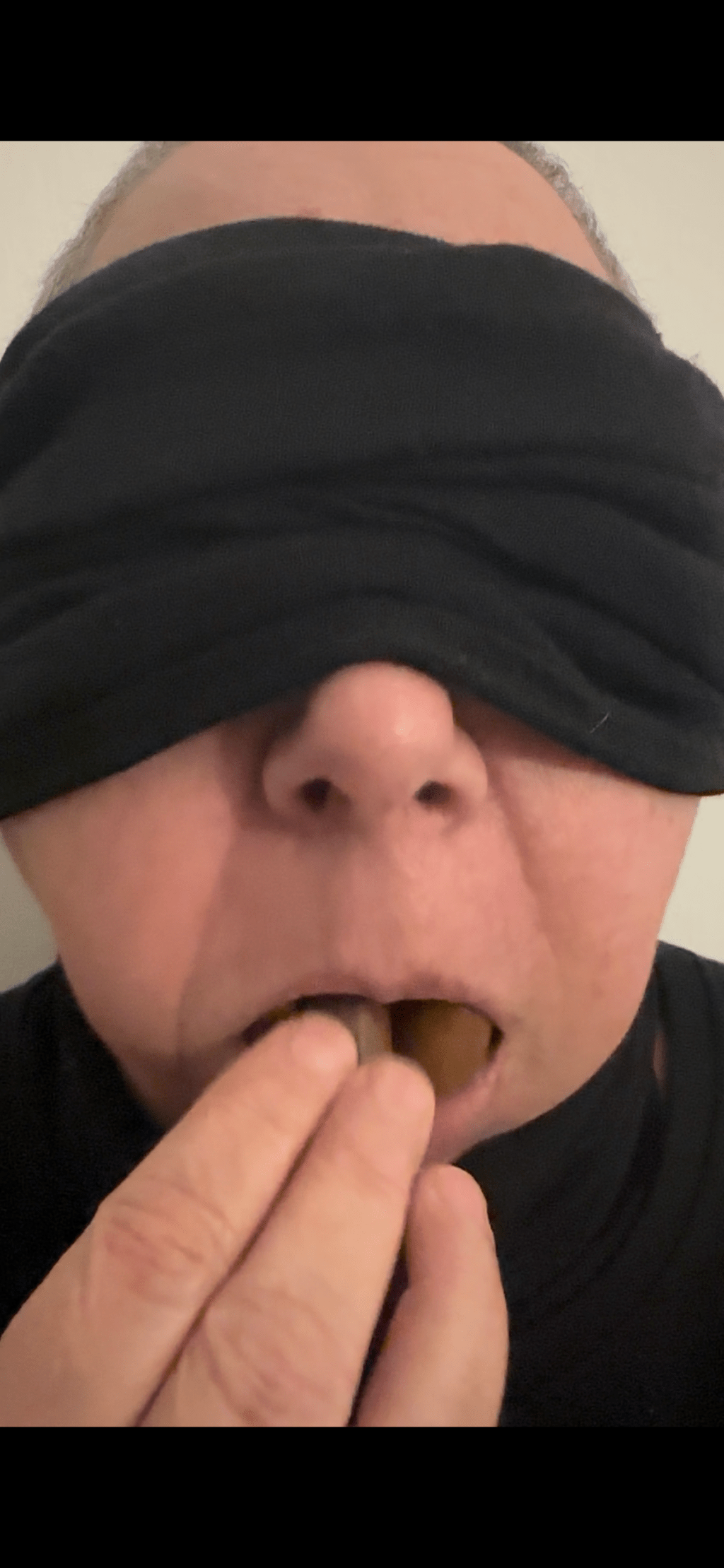

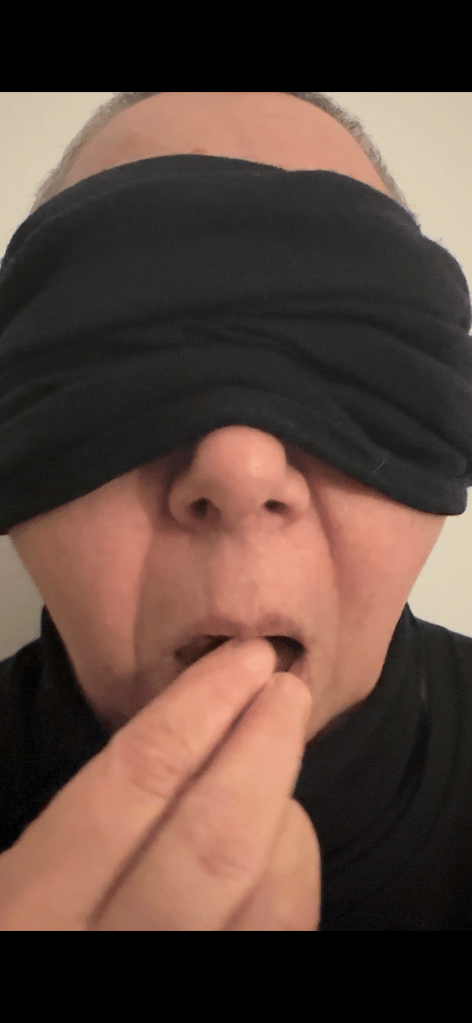

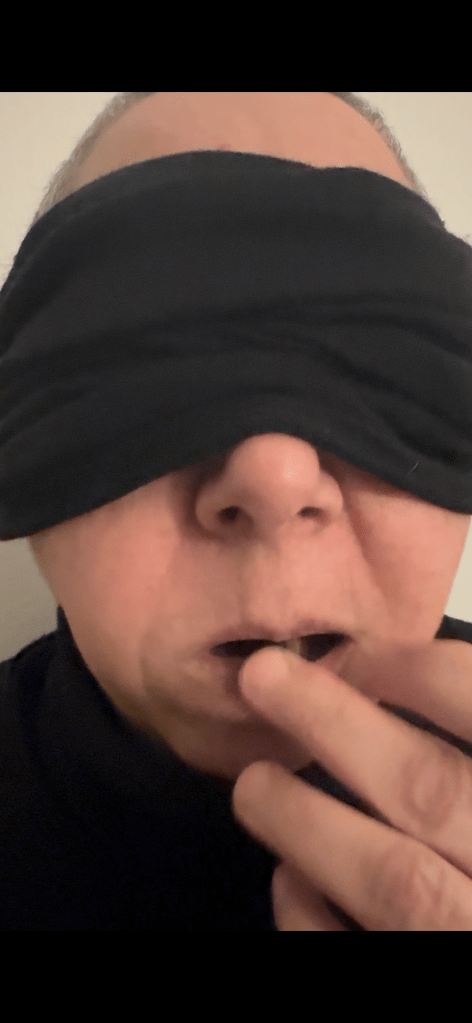

Video credit:Izadora Reis;Editing credit:Devora NeumarkSaying I didn’t enjoy watching it would be an understatement.

I found it physically challenging to sit with this artifact. Every time I approached my computer to rewatch the video and try to write a response, I couldn’t stay still. I was fidgeting, unable to watch it again.

I didn’t want to look at the photos. I didn’t want to write about it. I didn’t even want to think about it. As the deadline for my response approached, I grew increasingly anxious about my ability to respond.

The day before the deadline, as the sun set and the day slipped away from me once again, I decided to go for a walk and dictate my response. Moving – walking – helped me get my thoughts out. I wouldn’t say organized them. Although I later edited the text, I preserved much of its original rhythm and free flow of thoughts, in the exact sequence they exited my lips.

The previous night, struggling with falling asleep, I had looked up the etymology of settle:

settle (v.)

Middle English setlen, “become set or fixed, stable or permanent; seat, place in a seat; sink down, come down,” from Old English setlan “place in a fixed or permanent position; cause to sit, place in a seat,” from setl “a seat” (see settle (n.)). Compare German siedeln “to settle; to colonize.”

I wrote down as a note: “Does being unsettled mean decolonize?”

As I started walking, I thought about what it means to be settled. I walked through my densely populated neighborhood, headphones on to dictate my thoughts, tuning out the sounds around me.

I began with the idea of settled and unsettled. When we look at settled, we see it means staying in one place. Unsettled is about movement, instability, shifting between places. So why do we value stability? Why do we need to “settle down”? Why do things need to settle?

I think of letting the dust settle, envisioning the tiny specks drifting down and leaving the air pure and translucent.

Are things ever truly settled? Are we? And when we are, does it mean we’re in a comfort zone? Is that the goal – to find comfort?

As my feet advance on the sidewalk, I try to recall and express the feelings I had while watching this video. In truth, I could hardly bring myself to watch it. I feel disgusted, anxious, just thinking about it. My stomach turns, and I feel unwell in my body. I need to move my thoughts. I need to move. My emotions need to shift to make room for taking in this video. I am unsettled, and this sense of unrest has stayed with me all week as I’ve struggled to come up with a response.

I think of the rhythm Devora and I set up for this project: seven days for each of us to respond – Devora to the prompt, and me to the artifact they send. For both of us, it means living with the word for a week. In my case, I carry an photo, a video, or a recording shared with me. As I go about my everyday life, I process my experiences through the lens of that artifact. This word, this image, this sound becomes my focus for that period.

Coincidentally, this week I encountered many moments of feeling unsettled. From the struggle to hold a pose in yoga, to the physical discomfort after a vaccine reaction, to emotional turbulence in social dynamics. I kept returning to this idea of unsettlement. These moments took me out of my comfort zone. They touched my ego and my self-confidence. Yet in each experience, I found an opportunity: to work with my body, to strengthen my immunity, to reflect on how I want to interact with others. This sense of being unsettled became a source of healing.

Indeed, Devora mentioned that the gesture I found disturbing was actually healing for them.

Their interaction with AI provided various interpretations of how this act could be seen as healing and what symbolic meanings eating acorns might carry. This brings us back to how generative AI, like ChatGPT, actually functions. ChatGPT offered interpretations that were, as Devora noted, fairly accurate. But it is important to remember that what ChatGPT does is essentially predictive – it generates the next word based on probabilities and patterns from the prompt, rather than providing inherent meaning or true insight.

Devora’s reply here: “While it’s true that ChatGPT doesn’t provide inherent meaning or true insight, the same can be said of any source of information. Meaning and insight arise from the human mind, shaped by somatic awareness and personal context, which allow patterns to resonate and deepen in unique ways.”

Are generative AI systems like ChatGPT “settled” or “unsettled”? While AI cannot be unsettled “E”motionally, it is constantly “IN” motion, adapting with each prompt and rarely producing the exact same response twice. So, is it truly stable?

This brings me to wonder: how does the concept of being “settled” apply to technology? We expect our technology to be stable: accessible at all times, dependable, performing exactly as we want. But is it reasonable to expect the same from humans? From ourselves or others?

How does this notion that what is “settled” is desirable, and what is “unsettled” is to be avoided, shape our perceptions? This perspective extends to how we think about migration and those who live nomadic lifestyles, as we’ve previously explored. Are we fearful of people who are “unsettled,” or as we might say, “unstable” or even “unhinged”? And what connections lie between these terms?

What, then, is the difference between “unsettled” and “uprooted”? When we talk about migration, it is often the experience of being uprooted, rather than simply unsettled, that creates a sense of loss and disorientation.

As I say this, I pass by many trees. I observe them, letting them influence my thoughts.

As we consider the sequence of prompts we’re exploring, the idea of “settlement” contrasts with being “bound to earth.” To be bound to the earth implies roots that hold us firmly in place, while Unsettled introduces the notion of movement and instability.

Acorns embody this dichotomy – they fall to the ground, and some take root, creating new life.

There are countless acorns, yet only a few will become oak trees. (After my walk, I researched this and learned that only one in 10,000 acorns grows into an oak tree.)

Those oaks, if left undisturbed, may stand rooted for hundreds of years.

The rest of the acorns meet different fates: some are eaten, others decompose, offering nourishment to wildlife and soil. They travel with the elements. (Some might be picked up by a passerby on a fellowship, boiled, put in their mouth, filmed, and become an international internet sensation.)

We asked AI to tell us how acorns can heal us. This reflects an interesting aspect of our relationship with the planet and its resources – we often ask what they can do for us, without necessarily considering what we can do for them, or whether it’s right to take them from where they’ve fallen.

Interestingly, oak trees produce such an abundance of acorns for a reason. (Or so I read after my walk.)

During “mast years,” they produce thousands of acorns, providing abundant food for animals like squirrels and birds. The goal is for some acorns to be left behind or forgotten, giving them a chance to grow. In the following year, the trees produce few or no acorns, as the previous bumper crop requires significant energy. This cycle controls wildlife populations, which decline when food becomes scarce.

(I’m still walking.)

What is the difference between settling and grounding? One of the qualities identified by AI for the acorn is grounding – a sense of being rooted in one’s body. But can we be grounded yet unsettled? The oak tree offers a model: its roots are firmly in the earth, but its branches sway in the wind. Its leaves change colours, fall, regrow. It creates acorns that may or may not carry on its legacy.

When we speak of involuntary migrants, are we taking some agency away from them when we use the term displaced? This labels them as passive, as if the unsettled state is happening to them without choice. Yet many of those who leave dangerous or unstable places still make a choice – to leave. They may face serious consequences for staying, yet they still have that option. Often, they also have some choice, however limited, about where to go or what their ultimate destination or life project might be.

However, even once they reach their projected destination, it may not meet their expectations or feel like a true home. They might not find the lifestyle, job, school, community, food (or other nourishment) they had hoped for, and so they may remain unsettled for a long time. Unsettled isn’t just a temporary stage in the life of a migrant. Or, really, in anyone’s life!

So, how do we embrace unsettled? How do we make choices despite discomfort, find growth within it? How do we engage meaningfully with those who are unsettled? How can we accept their state of unrest, support their healing, and recognize that what feels uncomfortable to us might actually be comforting to them?

The fact that I dictated these words directly into voice-to-text, without recording first, adds a specific rhythm to how this response flowed from my mind to the page, bypassing my fingers entirely.

This approach also feels connected to the previous response, which focused on hands. For the Scorched video, I chose to add sound as my response. But I initially didn’t want to interact at all with this new video – let alone upload it into editing software and make changes.

However, as I say these words, an idea comes to me. I stop talking and begin recording the sounds around me – the city, unsettled, moving. All these sounds I ignored to focus on my words: cars racing by, passersby talking, my own footsteps.

I decide to layer these sounds onto the video. Here is my response.

The sound of movement makes the video easier for me to digest.

I realize Devora is sitting in their video. Sitting at a computer and watching their video is an equivalent of being face to face, staring at someone stuffing their mouth. This breaks a lot of codes I was taught. Walking away from it was an instinctive reaction.

Devora writes “During the performance my eyes and ears were covered and so my senses were more inward, relying on taste, touch, and smell. Yet, you, in your response, fall heavily into making sense of the performance artifact through sight and audio cues and that might be one of the differences in our perceptions.”

It is also true that the video didn’t allow me to access their internal perceptions. While the word file provided some interpretations, I didn’t connect with them having known they were generated by an AI. I understand that others who read the document had a more positive reaction to what generative AI can produce in terms of text and information. From my perspective, it felt like looking an a plastic acorn, looking very similar to a natural one, but overly shiny and painted in an unnatural colour. I realize now that reading the text left me with a sense of unease.

The sounds on my walk made me think of the movement a displaced person might encounter. Their feet moving. Vehicles going by. Other people present on their journey, but living different experiences. While not all displaced people will come to urban areas, they will all encounter some of these sounds. And perhaps just as I was turning these sounds off while concentrating on my answer, they will also not pay attention to them.

Turning these sounds back on and adding them to the video represents for me presence in the moment. This is actually very similar to what Devora experiences in their performance. While being unsettled in front of the video, I wasn’t really appreciating the video: I was focusing on my own reactions. I wasn’t in the moment. I wasn’t in that room. I wasn’t in my body. I was judging. I was reacting.

The sounds of the city represent taking in the performance from where I am. Taking it in within the context of my own life and experiences, without shutting them off.

Around 50 seconds, we can hear a passerby say “l’environnement déteint” : the environment changes the colour of the object in it. And certainly our environment is very important for our perceptions. Particularly our perceptions of an artistic performance. I would not have had the same experience have my environment been different.

Perhaps for you these sounds are irrelevant or distracting. What sound, smell, touch, movement would you need to add to digest this performance?

As for me, I come home to my body. I’ve created another response. It’s settled.

Leave a reply to Prompt 5: Scattered – Displacement Codes – Contemplative Performance and the Climate Crisis Cancel reply